May 16, 2022

James Lawrence, a prude feminist

Despite a chaotic editorial journey and being heavily hindered by censorship, this work by a young Englishman, who claimed to follow Mary Wollstonecraft, would have a considerable influence on some of Europe's most prominent minds, including Percy and Mary Shelley, Goethe, Schiller, Aaron Burr, Thomas Carlyle, and Flora Tristan...

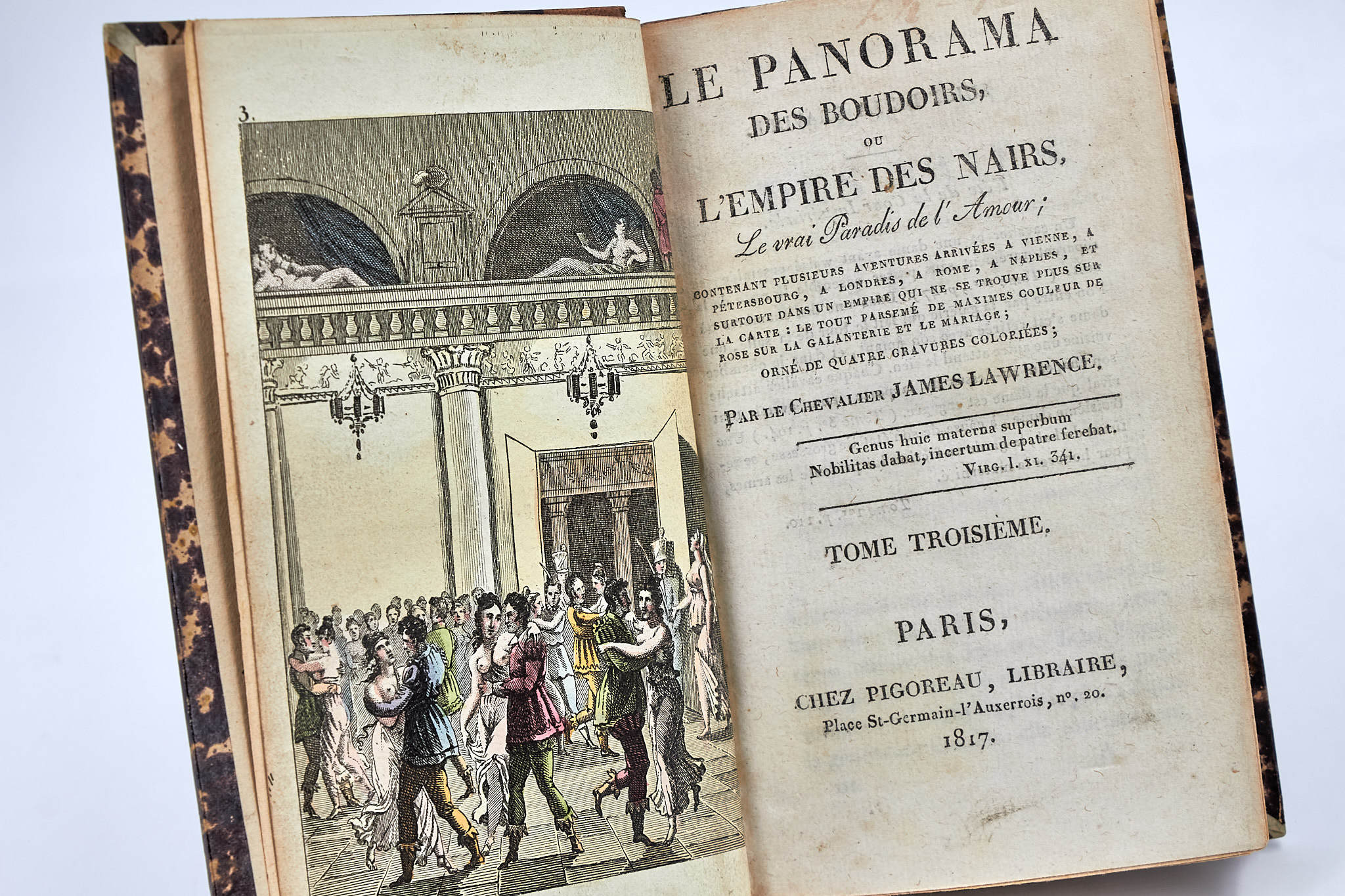

12mo format, evocative title of licentious pleasures and suggestive engravings delicately enhanced by hand to accentuate their sensuality, the four small volumes of this Panorama of Boudoirs, discreetly bound, do not surprise the experienced bibliophile or the accustomed bookseller, the work of this Englishman – a pseudonym? – seems to be one of those numerous mischievous erotic works published clandestinely and which collectors call *curiosa*.

And yet…

This long novel, disguised as an erotic collection, is in fact one of the most important feminist texts of the early 19th century. Despite a chaotic editorial journey and being heavily hindered by censorship, this work by a young Englishman, claiming to follow Mary Wollstonecraft, would have a considerable influence on some of Europe's most prominent minds, including Percy and Mary Shelley, Goethe, Schiller, Aaron Burr, Thomas Carlyle, and Flora Tristan.

Although published in three versions, German, French, and English, each being a complete rewrite of the work by the polyglot author, this major and subversive work was quickly removed from bookstore catalogs, and its author disappeared from literary history from 1840 until the late 1970s.

“Today, after having been known only to specialists of Shelley, Lawrence is beginning to gain visibility within works on English radicalism. (…) He is prominently placed among the English feminist radicals of the 1790s and (…) is considered one of the forerunners, along with Shelley and Owen, of the fight against marriage and for sexual reform.”

(Anne Verjus, Can a society without fathers be feminist? The Empire of the Nairs by James H. Lawrence.)

Despite the dozen editions published in the 19th century, we have found no copies offered on the international market.

Lawrence was barely 18 when he wrote “a first essay on the 'system' of the Nairs, a matrilineal society located on the Malabar coast in India, in which marriage and paternity have been abolished. The young scholar also adds a severe critique of the sexual and marital practices of his contemporaries. One of his professors sends the manuscript to Christoph Wieland, editor of the journal Der Neue Teutsche Merkur. After encouraging him to translate it into German, the “German Voltaire” publishes it (anonymously) in his journal in June 1793, in Weimar. The text is immediately translated by the Newgate radicals, who publish it without his consent and without the author’s name, first in 1794, then with his name in 1800.”

Enthusiastic about the esteem his essay garnered, James Lawrence composed in 1800 a first fictional version illustrating his theses. Upon reading the manuscript, Schiller reportedly encouraged him to rewrite it in German. Thus, the first version of the novel was published in German in 1801 under the title Das Paradies der Liebe and then in 1809 under a new title: Das Reich der Nairen or Das Paradies der Liebe.

Present in France in 1803, James Lawrence was imprisoned, like most Englishmen, and was detained in Verdun for several years. It was under these circumstances that he began the complete rewriting of his novel directly in French. He titled it L'Empire des Nairs, ou Le Paradis de l'amour and had it published in 1807 by Maradan, the publisher of Wollstonecraft and Hays. Hardly off the press, the work, considered “offensive to public morals,” was seized by the police. The copies were returned on the condition that the entire edition would be exported. The work was then distributed in Germany and Austria, where it had Johann Wolfgang von Goethe as its ambassador, whom Lawrence had met in 1799 when the Romantic poet invited him to Weimar for the representation of Voltaire’s *Mahomet*. In his memoirs, Frédéric Soret recounts Goethe’s review of his friend’s work:

“According to Goethe, it is the work of a madman with much intellect, and he would think much better of Lawrence’s writings if his way of viewing the relations between the sexes had not become a sort of fixed idea in him.”

(Soret, Conversations with Goethe, 1932)

The friendship between the two men was not affected by this “obsession,” and in a letter to Thomas Carlyle in 1829, Goethe still referred to Lawrence as “a longtime friend.” Goethe was also the commissioner of the only portrait of J. Lawrence, done at the philosopher's request by Johann Joseph Schmeller.

The first English version, “translated, with considerable alterations, by the author,” was published in London in 1811 under a much more explicit title than the French version: The Empire of the Nairs; or, The Rights of Women. An Utopian Romance, in Twelve Books. It was republished in 1824 under a new title: The Empire of the Nairs; or, the Panorama of Love, Enlivened with the Intrigues of Several Crowned Heads; And with Anecdotes of Courts, Brothels, Convents, and Seraglios; The Whole Forming a Picture of Gallantry, Seduction, Prostitution, Marriage, And Divorce in All Parts of the World.

In France, it was only in 1814, after Napoleon’s fall, that Maradan was allowed to sell the copies repatriated from abroad, replacing the title page, although specifying at the bottom the printing date of 1807 (incorrectly printed as “1087”). Even after censorship was lifted, the distribution was so modest that today, no copies from 1807 survive, and only a few rare ones from 1814 exist in major European and American institutions.

In fact, in 1817, Pigoreau, Maradan’s heir, still held enough copies to consider reselling them. (Quérard mentions 1816, but this is clearly an error.) He decided to use a trick. Taking the original 1807 copies, he changed the title page again and replaced it with a very suggestive title: Le Panorama des boudoirs which he illustrated with four erotic engravings superbly enhanced in color, thus insinuating a completely different kind of literature.

The original French edition therefore appeared under three distinct title pages in 1807, 1814, and 1817. After a ban, an expatriation, and a first resale, it was only at the price of this final subterfuge that the last copies of this overly progressive work were sold. This idea was later adapted in various forms, as in 1831, when Baron d'Hénin published a rewrite of the text in 16 pages with a religious title: Les Enfants de Dieu ou La Religion de Jésus réconciliée avec la philosophie (he even announces in the preface that copies of the original edition are still available). Then, in 1837, the novel was again modified by the author and published under a vaudeville title: Plus de maris ! plus de pères ! ou Le Paradis des enfants de Dieu.

In fifty years, this multifaceted work saw at least seven publications in French – and a dozen in the three languages. However, we could only find two copies offered for sale of the French edition (one from 1814 and one from 1817), presented as erotic works following the erroneous description in the Bibliographie des ouvrages relatifs à l'amour by Gay-Lemonnyer.

These editorial adventures, as well as the almost complete disappearance of copies and the erasure of the author from literary history, testify to the obstacles placed in front of the emergence of a consciousness that would become the issue of the coming centuries: the necessary and always unfinished fight for equality and women's rights.

While France chose simply to ban the book, invoking its immorality and the danger it represented for French readers, England, already grappling with the writings of Mary Wollstonecraft, allowed the publication of this new incendiary work but unleashed criticism. In 1811, The Critical Review devoted several biting pages to it, expecting that its readers, and especially its female readers, would reject with “disgust and indignation” a text as “absurd, improbable, indecent, immoral, and only fit for the fire” (Anne Verjus, ibid).

Thus, thanks to these maneuvers, the book passed almost unnoticed by the general public, despite international distribution. The circulation of Lawrence’s novel was therefore confidential, but its influence was major in progressive intellectual circles.

The first convert is undoubtedly Mary Wollstonecraft's son-in-law, poet Percy Shelley. Part of his work, especially Queen Mab (1813), Laon and Cythna (1817), and Rosalind and Helen (1819), would be inspired by this defense of free love and more particularly by some scenes from the novel. Perhaps he recommended it to his new conquest and future wife, the very young Mary Godwin Wollstonecraft, who cites the work in her journal from September 27, 1814, and in her 1814 reading list, just after meeting Percy Shelley.

Far from sharing her young companion’s enthusiasm, the 17-year-old girl proves to be highly critical of James Lawrence’s work. The future Mary Shelley was no less profoundly shaken by this novel, which would have a major influence on the writing of her masterpiece, Frankenstein. In her study, The "Paradise of the Mothersons": "Frankenstein" and "The Empire of the Nairs.", published in The Journal of English and Germanic Philology, (1996), D.S. Neff analyzes the influence of James Lawrence on Mary Shelley and shows "that a close reading of both novels reveals that Mary borrowed several plot elements and themes from the Nairs. She nevertheless felt compelled to write an anti-Nairs, a monstrous parody of Lawrence's romance, while Percy Shelley used *The Nairs* as a source of inspiration for his poems written during the creation of *Frankenstein*."

Follet Newsletter, a singular note

on the ever-changing world of books.