January 27, 2026

What is an Incunabula?

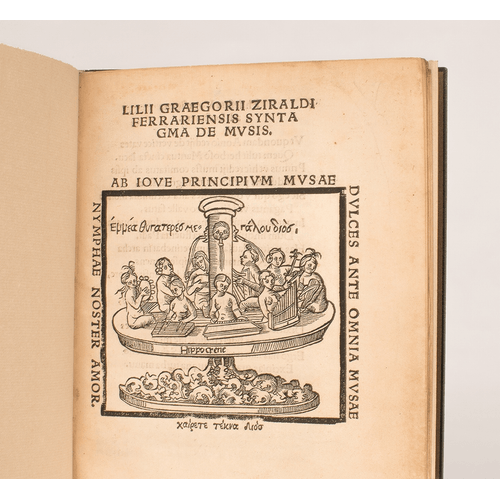

An incunabulum is the "cradle" of the printed book. This elegant term designates all books printed between 1452 and 1501.

These dates are not arbitrary. The date of the invention of printing, although imprecise (between 1452, the date of Gutenberg's very first impressions of ephemera, and 1455, the release of his famous Bible known as the B42), marks the beginning of competition between the manuscript book, that is to say hand-copied by clerks, and mechanical printing using the movable type invented by Gutenberg.

The revolution was spectacular: a scribe copied an average of three copies per year, while printing, from its very inception, made it possible to produce more than 150 copies (the print run of the Gutenberg Bible is estimated at between 158 and 180 copies) in just a few weeks (in reality, this first book took at least two years, but well, it was the beginning...). By 1500, the print run of an edition could reach 1,000 copies.

During these 50 years of early youth, printing, born from a failed partnership between Johannes Gutenberg, Peter Schoeffer and Johann Fust, would enable the publication of 29,000 texts, and almost all of Europe would be conquered by the lightning-fast spread of this cutting-edge technology which offered access to all purses - well-filled ones - to ancient, medieval and sacred writings, but also to the modern and sometimes sacrilegious ideas of humanists, scientists, pamphleteers, and new religious orthodoxies. The first printed editions of texts previously circulating in manuscript form would be called "editiones princeps". New works, born under the press, would henceforth be termed "original editions".

POST-INCUNABULA: THE END OF THE BEGINNING

At the beginning of the 16th century, a second revolution occurred which would mark the end of the book's infancy and its emancipation from the customs and rules established by 1,400 years of the codex (that is, the book formed of folded sheets assembled in gatherings, which replaced the rolled parchment volumen at the beginning of our era). From 1501 onwards, therefore, the book rapidly transformed to acquire its current composition:

- Appearance of the title page. Until then, information about the author, date and even title was only indicated on the last page called the "colophon".

- Pagination: the manuscript book was written after stitching, numbering was unnecessary. The first printed books required numbering of the gatherings to avoid errors during binding. The invention of page numbering, technically unnecessary (and moreover often erroneous in these early years), was an innovation for the reader's convenience.

- Abandonment of the illuminated initial. The last vestige of manuscript writing, most incunabula left blank the first letter of each chapter, which an illuminator would "rubricate", that is to say paint in red (ruber) or other colors.

- Systematization of Roman type in a part of Europe which exchanged the elegant Gothic letter for the efficient Italian letter, whose clear, refined and legible design was inspired by humanist philosophy. The book was no longer a work of art; it became an instrument of knowledge.

- Page layout: new margins, new punctuation, invention of paragraphs, appearance of the accent, of italics, creation of indentation, typographic standardization... the book underwent an internal makeover.

- New economic and political marks: printer's mark, Royal Privilege, legal deposit, printed dedications...

From 1501 onwards, the book was no longer conceived as a simple mechanical transposition of the manuscript, but as a full-fledged vehicle of thought, responding to its own logic and unprecedented imperatives: new readership (in 50 years, more than 7.2 million books had been printed in Europe, representing as many new readers), unprecedented dissemination of new ideas (humanism, Protestantism, sciences...), commercial competition, state surveillance and above all the unbridled inventiveness of publisher-printers.

Of course, these developments were not simultaneous and it took a good additional half-century for the book to complete its adolescent transformation. Thus, copies printed during the early years of the new century (1501-1530) are at least granted the designation of: post-incunabula.

See our selection "Incunabula and rare books from the 15th and early 16th century"

Follet Newsletter, a singular note

on the ever-changing world of books.