Suspension points are among Céline’s preferred forms of punctuation. The writer went even further and left blanks in his novel Mort à Crédit. It is an exceptional feature of the very rare tirages de tête copies of his masterpiece. A note below the dedication page of such copies states :

“At the request of the publishers, L.F. Céline has deleted several sentences from his book; the sentences have not been replaced. They appear as blanks in the book”

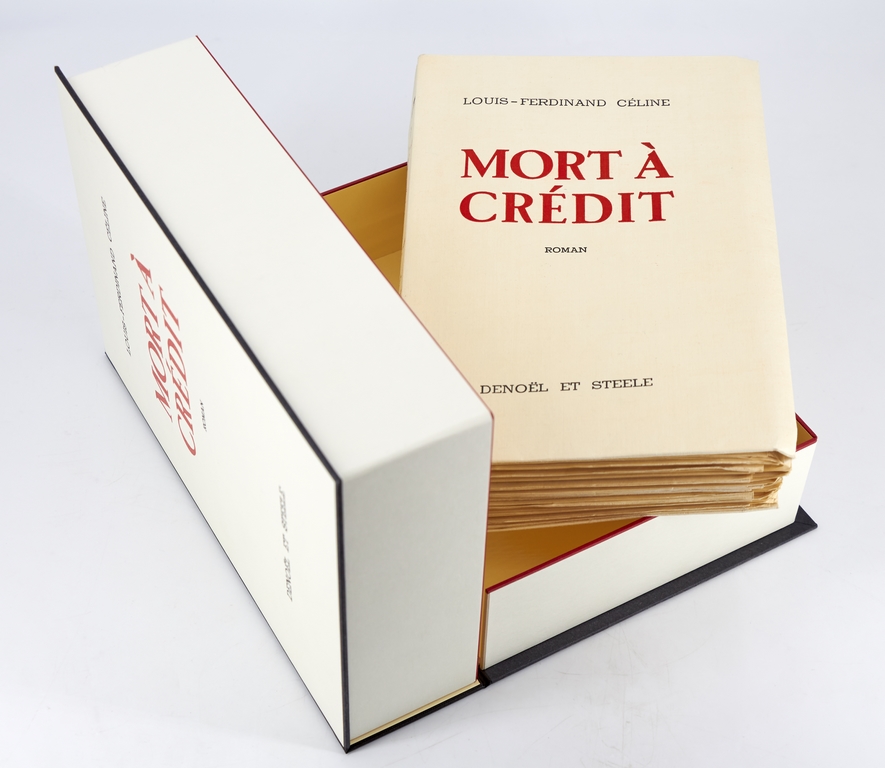

The 1,012 first edition copies of

Mort à crédit, published in 1936, include a few blank spaces scattered throughout the text. Deleted words, sentences or paragraphs are emphasized by these vacant spaces.

Instead of being the result of official censorship, these "holes" are the work of Céline himself. When his publisher Denoël criticized some passages deemed too salacious, Céline had the genius idea of replacing details of certain lewd scenes with much more suggestive approach: by removing the text altogether, letting the reader's imagination fill in the blanks.

A true pornographic reinterpretation of Diderot's address to Sophie Volland: “every place there is nothing, you should only read I love you”, Céline's silent invitation to his readers is much more powerful that the literary witticism it replaces.

Such is the case with one of the first “cuts” in his novel:

"

un soir au mur il y eu un scandale. Un sidi monté

Il s'était fait finir ! Mais oui ! qu'était certaine la Vitruve. En commentant ça."

A mysterious and provocative veil was placed over what is fact a description of a pedophile rape. The unredacted passages were eventually published in 1981, as part of the second Pléiade edition of Céline’s works.

Originally a product of editorial caution, Céline created a real work within the work, since the main subject of the deleted passages are about "voyeurism", a key theme in Céline's writings. It's doubtful whether Robert Denoël is really responsible for deleting said passages? which Céline himself promoted:

“With the full text of the novel, it's quite simple: we were going to be prosecuted for indecent exposure. We would have missed out on the Goncourt [prize]. We wouldn't have escaped prosecution”.

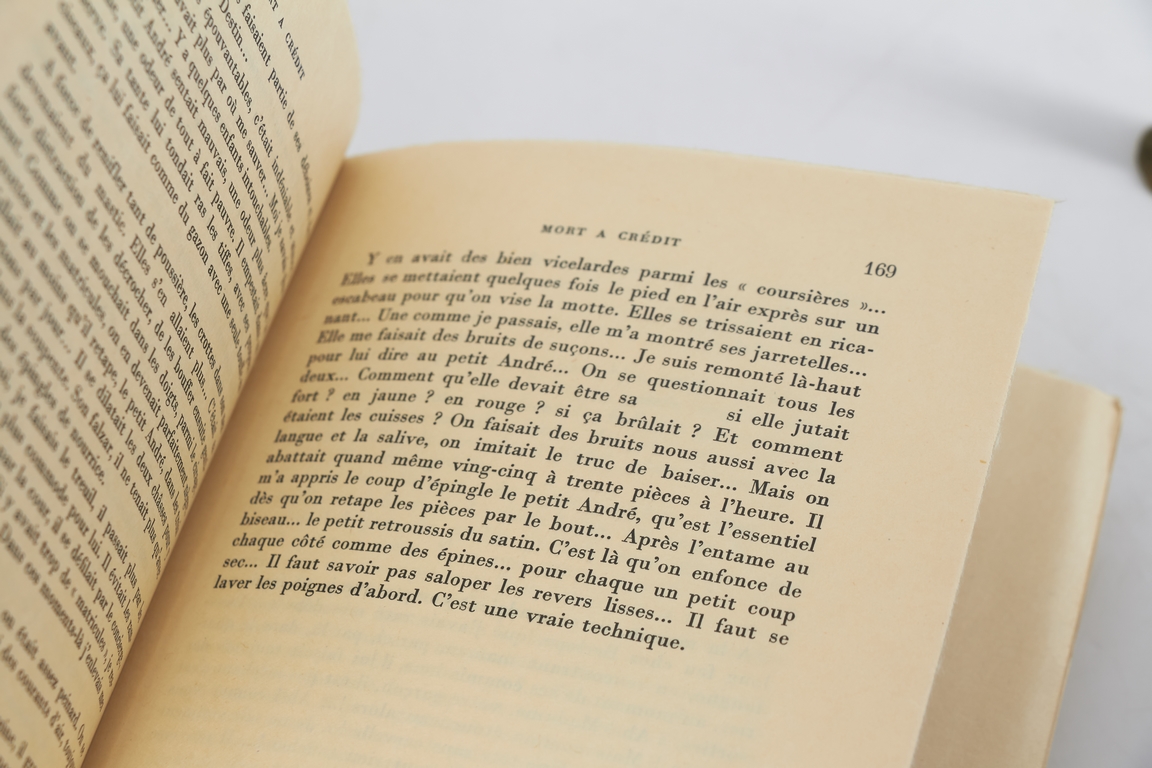

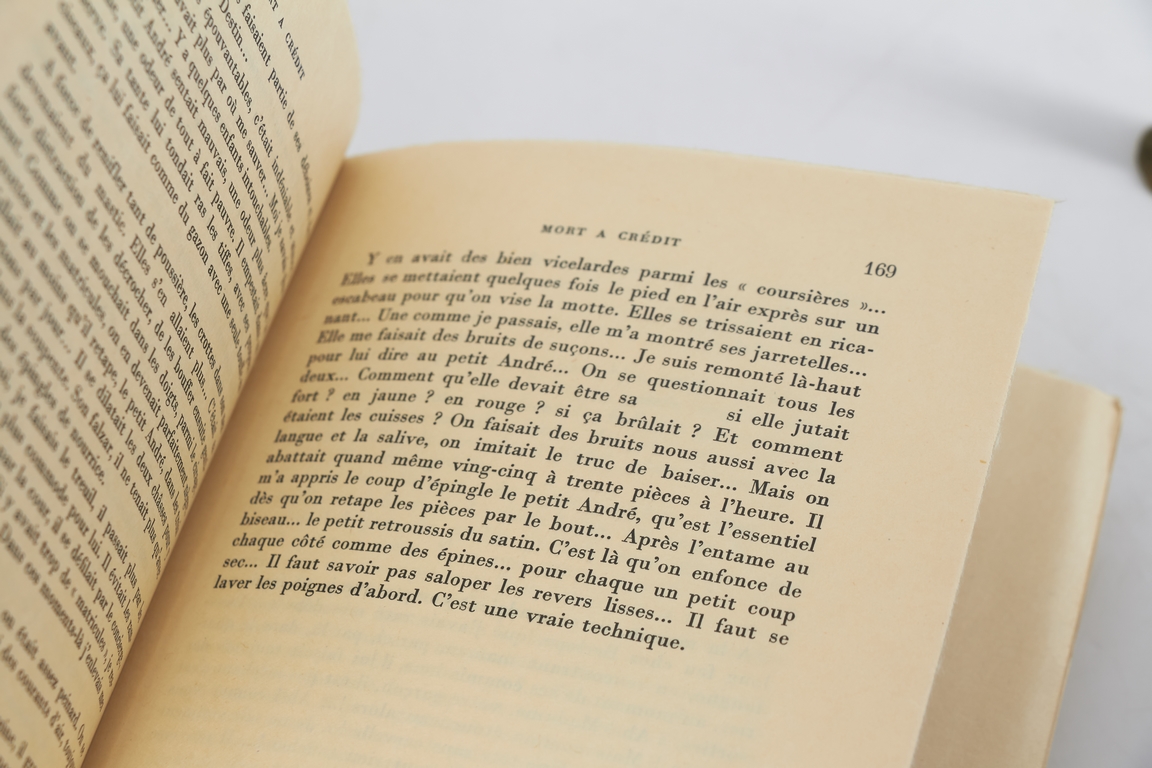

In reality, the cuts are nowhere near as significant as he suggests. In fact, they correspond to a strange narrative logic. After an opening on page 29, the cleverly peppered blanks are due solely to the airy layout of the chapters and short paragraphs. The reader has to wait until page 169 to discover a second hole in the text, quite unnecessary in view of the eloquent context:

As unobtrusive as a printing error, the deletion of the simple word "craque" in: “Comment qu’elle devait être sa si elle jutait fort ? en jaune ? en rouge ? Si ça brûlait ?”, is clearly just a stylistic effect to grab the reader's attention.

30 pages later Céline really begins to leave holes in the text, until the climax pages 222-223, which gives the impression of intense censorship:

« Oh le gros petit dégueulasse… il regardera plus par les trous ! …

J’osais pas trop en ôter… »

Céline explicitly confesses to this pseudo-self-censorship – as a writer who made suspension his literary identity. By no means a victim of his publisher's cowardice, Céline is, in all likelihood, the real reason behind this audacious "surgical operation" (to use Baudelaire's expression), and a knowing accomplice of his publisher Denoël. The writer also points out Denoël’s dislike of his famous suspension points:

“Denoël, the three little dots didn't appeal to him. Frightened, he was. Reproving. We were leaving good tradition, repudiating all form: it was no longer attached to anything... Ah, this time, my publisher was no longer ensuring the novel’s success! He had to absolve himself of any responsibility. To walk away from the gambling table...

‘Dear Céline’, he began, ‘I'm afraid you've made a mistake... Let's see, even for a man like you, there are limits, a measure to be kept!’

His features were severe, his gaze perplexed, his voice anguished (but very dignified). Brave Denoël! ‘My good friend, I warn you. And then there was something else. These passages were too daring, really too daring! Of course, art has its rights, but still...’ ”

By mixing elusive punctuation and crude vocabulary in Denoël's reproaches, Céline underlines the correlation between the unspoken and the overly explicit. He invites the reader to reinterpret the "few empty spaces" as ostensible marks of style, to the great delight of his adventurous publisher.

The double-page centerfold, rigged with holes, is enough to produce the desired effect, and "censures" then disappear completely, as if Denoël had nothing more to reproach the style of its protégé, whose art could once again take its rightful place with impunity.

It's no coincidence, moreover, that Céline and his publisher chose to print two versions of the deluxe copies, one uncut (to prove the existence of the scandalous deleted parts) and the other with those precious "blanks" that aren't blanks at all.

But it is undoubtedly at the heart of the work itself that we find a subliminal evocation of the complicity between and publisher:

"The two of us, Robert [Denoël] and I, it was time to climb onto the cooker's stove to watch the show... It was a well-chosen spot to perch... We were diving right onto the page..."