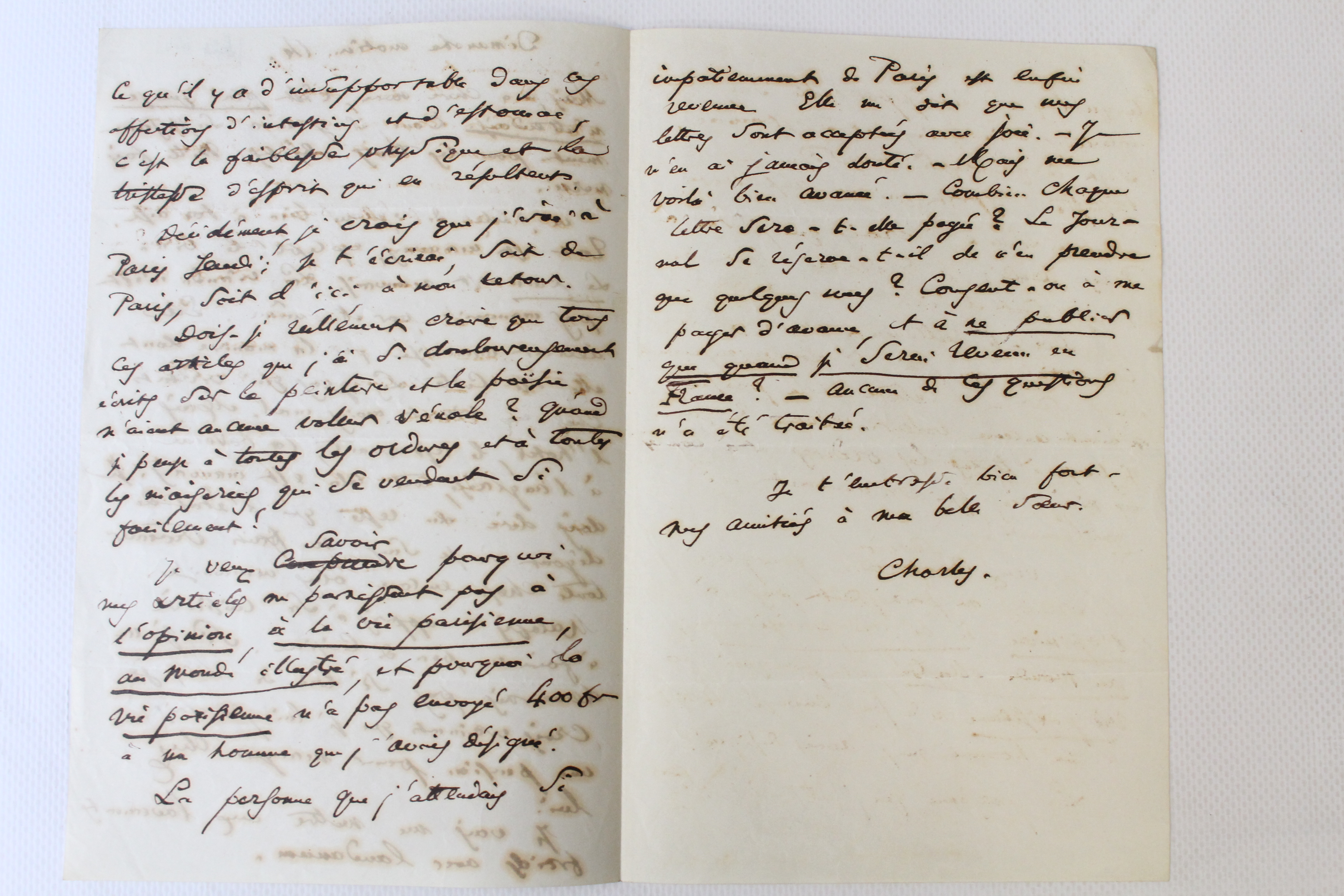

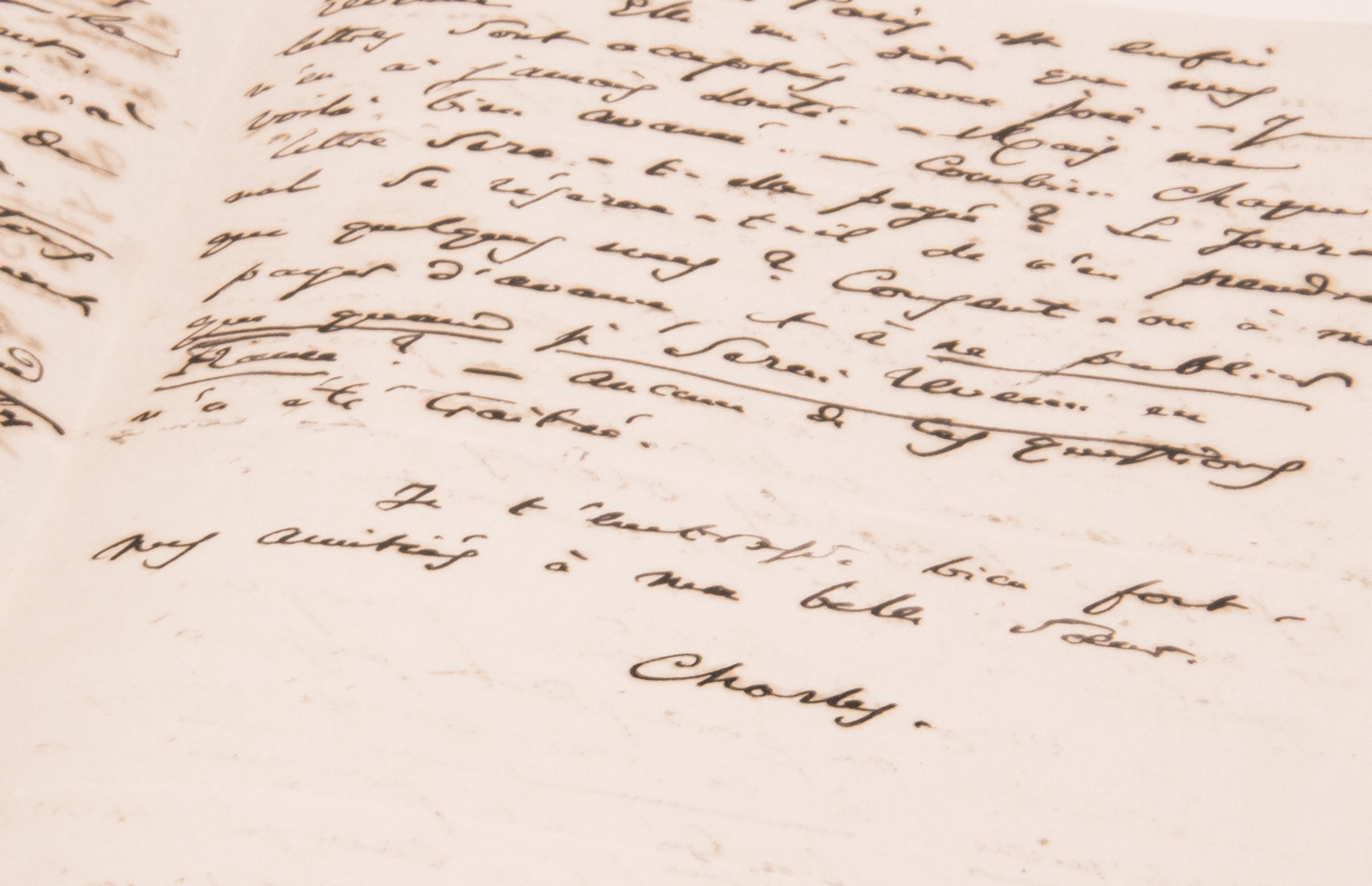

Autograph letter signed addressed to his mother by a fading Baudelaire: “L'état de dégoût où je suis me fait trouver toute chose encore plus mauvaise”

N. p. [Bruxelles] Sunday morning 14 [August 1864], 13,4 x 20,6 cm, 3 pages on a folded leave

Autograph letter signed in black ink, addressed to his mother and dated “Sunday morning the 14th.” A few underlinings, deletions and corrections by the author.

Formerly in the collection of Armand Godoy, n°188.

A fading Baudelaire: “The state of disgust in which I find myself makes everything seem even worse.”

Drawn by the promise of epic fame, Baudelaire went to Belgium in April 1864 for a few conferences and in the hope of a fruitful meeting with the publishers of Les Misérables, Lacroix and Verboeckhoven. The meeting didn't happen, the conferences were a failure and Baudelaire felt boundless resentment for “Poor Belgium”. Nonetheless, despite numerous calls to return to France, the poet would spend the rest of his days in this much-castigated country, living the life of a melancholic bohemian. Aside from a few short stays in Paris, Baudelaire, floored by a stroke that left him paralyzed on one side, would only return to France on 29 June 1866 for a final year of silent agony in a sanatorium.

Written barely a few months after his arrival in Brussels and his initial disappointments, this letter shows us all the principal elements of the mysterious and passionate hatred that would keep the poet definitively in Belgium.

In his final years in France, exhausted by the trial of The Flowers of Evil, humiliated by the failure of his candidacy to the Académie Française, a literary orphan after the bankruptcy of Poulet-Malassis and disinherited as an author by the sale of his translation rights to Michel Lévy,

Baudelaire was above all deeply moved by the inevitable decline of Jeanne Duval, his enduring love, while his passion for la Présidente had dried up, her poetic perfection not having withstood the prosaic experience of physical possession. Thus, on 24 April 1864, he decided to flee these “decomposing loves”, of which he could keep only the “form and the divine essence.”

Belgium, so young as a country and seemingly born out of a Francophone Romantic revolution against the Dutch financial yoke, presented itself to the poet phantasmagorically as a place where his own modernity might be acknowledged. A blank page on which he wanted to stamp the power of his language while affirming his economic independence, Belgium was a mirror onto which Baudelaire projected his powerful ideal, but one that would send him tumbling even more violently into the spleen of his final disillusionment.

Published in the Revue de Paris in November 1917, without the sensitive passage about his cold enemas, this emblematic letter evokes all of Baudelaire's work as poet, writer, artist and pamphleteer. The first such reference is via the reassuring, mentor-like figure of the publisher of The Flowers of Evil, Poulet-Malassis: “If I was not so far from him, I really think I'd end up paying so I could take my meals at his.” This is followed by a specific reference to the “venal value” of his Aesthetic Curiosities: “all these articles that I so sadly wrote on painting and poetry”.

Baudelaire then confides in his mother his hopes for his latest translations of Poe which, to his great frustration “are not getting published by L'Opinion, La Vie Parisienne, or in Le Monde illustré”. He concludes with his Belgian Letters, which Jules Hetzel had just told him had been, after negotiations with Le Figaro, “received with great pleasure.” Nonetheless, as Baudelaire literally underlined, they were “only to be published when I come back to France.”

His perennially imminent return to France is a leitmotiv of his Belgian correspondence: “Certainly, I think I'll go to Paris on Thursday.” It is nonetheless always put off (“I'm putting off going to Paris until the end of the month”, he corrects himself eight days later), and it seems to stoke up the poet's ferocity towards his new fellow citizens, Baudelaire taking pleasure in actively spreading the worst kinds of rumors about them (involving espionage, parricide, cannibalism, pederasty and other licentious activities. “Tired of always being believed, I put about the rumor that I had killed my father and eaten him... and they believed me! I'm swimming in disgrace like a fish through water.” “Poor Belgium”, in Œuvres complètes, II p. 855)

This eminently poetic attempt to explore the depths of despair in covering himself in hatred is perhaps most clearly seen through his sharing of his culinary difficulties with his “dear, dear mother”, the only sustaining figure who gave him “more than [he]'d expected”.

Read together with some of the finest pages of The Flowers of Evil, this excessive attention to the miseries of his palate reveal far more than simple culinary fussiness.

It is also hardly innocent that Baudelaire begins his recriminations with an exhaustive rejection of all food, with one notable exception:

“Everything is bad, save for wine”. This assertion is clearly not without reference to the “vegetal ambrosia”, that sanctified elixir in so many of his poems and above all a friend in misery, which drowns out the poet's sublime crime. “None can understand me. Did one /Among all those stupid drunkards / Ever dream in his morbid nights / Of making a shroud of wine?”.

“Bread is bad”. If wine is the incorruptible soul of a poet, bread, here underlined by the author, is his innocent and mortal flesh. “In the bread and wine intended for their mouths / They mix ashes and impure spit”, as Baudelaire says in Benediction. This is the poet-child who everywhere, in hotels, restaurants, English taverns, “suffers from this impossible communion of elements and thus presents his mother with an even more symbolic vision of his misery”.

Nonetheless, the man is always present, his carnal desires hidden beneath the misery of his condition. “Meat is not bad in itself. It becomes bad in the manner of its cooking.” How can we not, behind the apparently prosaic nature of this culinary comment, recognize the most permanent of Baudelaire's metaphors, present throughout the poet's work – A Carcass, To She Who is Too Gay, A Martyr, Women Doomed – the female body transformed by death?

“The sun shone down upon that putrescence,

As if to roast it to a turn,

And to give back a hundredfold to great Nature

The elements she had combined”

“People who live at home live less badly,” he continues, but Baudelaire doesn't want to be comforted and his complaining is nothing but an expression of the perfect correlations between his physical condition and this final poetical experience.

Of course, Belgium was not really to blame, but it was only to his mother that Baudelaire could make this rare and moving confession: “I must say, by the by, that the state of disgust in which I find myself makes everything seem even worse.”

Essentially, all the aggression he was to pour out on these cursed kinspeople was nothing but the echo of an older rancor that, in 1863, consumed his “heart laid bare.” To his mother's recriminations at finding her son's notes, Baudelaire replied, on 5 June: “Well! Yes, this much-wished for book will be a book of recriminations...I will turn on the whole of France my very real talent for impertinence. I need revenge like a tired man needs his bath.”

The “cold laudanum enemas” of Belgium were to be that bath for the tired poet, who found an occasion to combat, with a supreme wrath, this existential “disgust”. In the middle of a paragraph – the very one that would be cut by the Revue Française – Baudelaire attributes this, without naming the disease, to syphilis: “What is insupportable in these intestinal and stomach complaints is the physical weakness and the spiritual sadness that result from them.”

Madame Aupick's immediate concern at these all too sudden confidences led Baudelaire to lie to her about his actual state of health, which continued to get worse. Hence, in his following letter: “It was terribly wrong of me to talk to you about my Belgian health, since it affected you so deeply...Generally speaking, I'm in excellent health...That I have a few little problems...so what? That is the general lot. As for my trouble, I can only repeat that I have seen other Frenchmen suffer the same way, being unable to adapt to this vicious climate...And in any case, I won't be staying long.”

A superb autograph letter from a son to his mother, subtly revealing the poetical reasons for his final self-imposed exile, the inverted mirror of the first, enforced, wandering of his youth in the Mascarene Islands, the writer's only two voyages.

If the young man could somehow – we don't know how – escape to the far-off Reunion island, the old man nonetheless didn't dare leave Belgium, which was so close, and this melancholic letter augured the end of his days spent by the North Sea, as somber as his initial trip to the South Seas had been bright.